During my university placement year, while some of my friends were studying abroad, others living it up in big cities, and a few working on film sets, I found myself at home, glued to my laptop, logging data into a spreadsheet. Yep, for months, I was in a committed relationship with Excel, extracting energy inputs, outputs, BMI, and other various manipulations.

Was it glamorous? Absolutely not.

Was it thrilling? Not really.

But it mattered to me.

I chose my placement with an Appetite and Obesity Research Team because the topic was intriguing. Food systems and cultures have always fascinated me. Give me a Channel 4 Big Food exposé, or Tim Spectors latest book and I’m hooked.

So, while days spent extracting data weren’t exactly electrifying for someone like me (I prefer doing and creating, than reading about others doing and creating), the learning gained about the subject matter I have treasured.

The research team held monthly journal club meetings, educating me about the complex behavioural expressions of appetite and obesity. It was during one of these meetings, a discussion was held about childhood obesity, and I remember the notion being shared that the key to tackling the obesity epidemic lies in early childhood.

The UK government have recently announced a new measure: junk food ads will now only air after the 9pm watershed. The goal? To curb childhood obesity. On the surface, it seems like a step in the right direction and to an extent, it is. But here’s the thing: it won’t work.

Why Not? Let’s Start with the Numbers

The government claims the ban will remove 7.2 billion calories from children’s diets annually¹. That sounds impressive, right? Let me crunch the numbers for you.

- There are about 12.7 million children under 16 in the UK. (ONS Data)

- Divide 7.2 billion by 12.7 million, and you get 566 calories per child per year.

- Spread that over 365 days, and it’s 1.55 calories per day per child.

That’s less than the energy in a single tic-tac. One. Tic. Tac.

It’d be incorrect to assume the calorie reduction applies to all 12.7 million children under 16. So, let’s recalculate. If we consider that only children classified as obese are directly impacted by this intervention, the numbers shift.

Obesity prevalence is 9.6% at reception and 22.1% at Year 6, averaging roughly 16%. Applying this prevalence rate means about 2 million children might realistically be influenced by the policy.

- Divide 7.2 billion calories by 2 million children, and you get 3,600 calories per child per year.

- Spread over 365 days, this translates to nearly 10 calories per day per child.

This adjustment makes the per-child impact of the intervention appear slightly more appealing, but the broader question remains: how much of a dent can 10 calories per day make in a complex, multifactorial disease like obesity?

Examining the Evidence Base

To fully assess the plausibility of the policy’s claimed impact, we must establish the chain of evidence. Without robust data linking advertising exposure, parental purchasing decisions and excess calorie consumption, it’s challenging to contribute a significant reduction in calorie consumption to the advertising ban alone. A clearer evidence base is needed to validate the direct relationship between exposure, purchasing and consumption.

Obesity is multifactorial

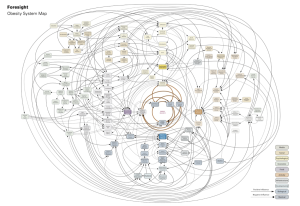

I protest the initiative further. Obesity isn’t the sum of “excess calories in” + “low physical activity”. It’s a multifactorial disease, meaning that obesity is caused by a complex interplay of multiple factors, rather than a single cause. Take a look at the image below – it’s the Foresights Obesity System Map², a comprehensive visual representation of the complex and interrelated factors contributing to obesity. Junk food advertising is one thread in this complex web, but it’s far from the only one.

Tackling a multifactorial disease requires a multidisciplinary approach.

Obesity is a disease

In the above paragraph I referred to obesity as a disease. As you read it, it may have struck you as odd or maybe even wrong.

Obesity is as much of a disease as asthma or chickenpox is. It is not a choice nor a lack of will. Yet unlike asthma or chickenpox, obesity is one of the few diseases where the individual is blamed. Interventions like this one unintentionally perpetuate this blame by framing the problem as one of individual behaviour and choice, rather than addressing the broader systemic and societal factors at play. Future approaches must adopt a multidisciplinary perspective that considers all the drivers of obesity. Only then can we design interventions that empower individuals without stigmatising them.

The intent is good, but the impact is less

As behavioural science consultants here at Caja, we’re all about applied behavioural science. Because while something (removing advertisements) may work in theory, the true impact (1.64 calorie reduction) is negligent.

I’ll give credit where credit is due, the intent is positive and is a stride towards some of the changes we need to make to tackle childhood obesity but it’s not enough to move the dial. Meaningful change requires an evidence-based approach that addresses causes and drives measurable outcomes. That’s where CognitivQI™ excels – combining behavioural science with a structured framework to create sustainable, impactful change.

Ready to make a real difference? Get in touch to see how CognitivQI™ can help you achieve lasting results.